Portable Landscapes: Unweaving the Iron Curtain

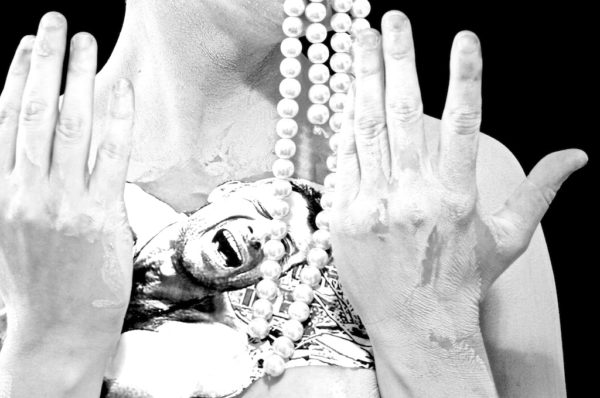

Margo Zālīte. On skin. 2009

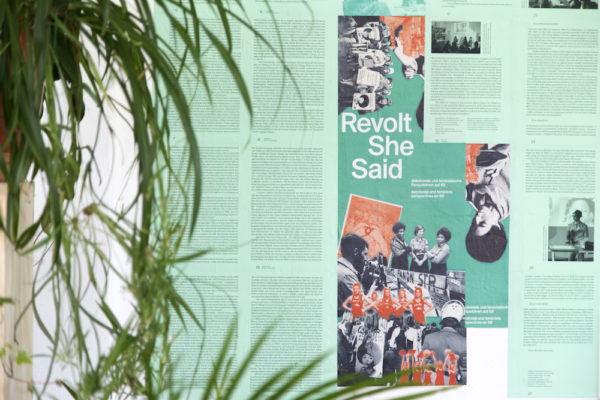

Ausstellungsansichten, Portable Landscapes. Unweaving the Iron Curtain. District Berlin, 2019. Fotos: Margarita Ogoļceva.

Ausstellung

mit Beiträgen von: Valdis Āboliņš, D’EST: A Multi-Curatorial Online Platform for Video Art from the Former ‘East’ and ‘West’, Inga Erdmane, Leonards Laganovskis, Elske Rosenfeld, Margo Zālīte, Nguyen Phuong Linh, Tuan Mami, Revolt She Said: decolonial and feminist perspectives on 68.

25. Juni – 25 Juli 2019, dienstags – donnerstags, 15 – 19 h

Eröffnung: 20. Juni, 18 h

Portable Landscapes: Unweaving the Iron Curtain ist Teil des Projekts Portable Landscapes des Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, das Geschichten von im Exil lebenden und emigrierten lettischen Künstler*innen im breiteren Kontext der Kunstgeschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts sowie den Prozessen der Migration und Globalisierung untersucht. Die kollaborative Ausstellung und das Programm bei District Berlin zeigen künstlerische und politische Ausdrucksformen von Diaspora und Dissidenz, welche binäre geopolitische Spaltungen, die als Eiserner Vorhang bezeichnet werden, sowohl während des Kalten Krieges als auch nach dessen Beendigung kreuzen, stören und auflösen.

Weitere Informationen zu Ausstellung und Programm in englischer Sprache hier.

PROGRAMM

Donnerstag, 20. Juni 2019, 18 h

Eröffnung

18.30 Uhr Rundgang durch die Ausstellung mit Künstler*innen und Kurator*innen: Inga Erdmane, Leonards Laganovskis, Ulrike Gerhardt, Andrea Caroline Keppler, Suza Husse, Antra Priede, Elske Rosenfeld und Andra Silapētere

7.30 Uhr At Home/Not at Home Künstler*innengespräch mit Margo Zālīte

Mittwoch, 3. Juli 2019, 19 h

D’EST at Scriptings: Lene Markusen: Sisters Alike. Female Identities in Post-Utopian

Screening and discussion

Location: Scriptings, Kamerunerstr. 47, 13351 Berlin

Freitag, 12. Juli 2019, 19 h

Revolt She Said: decolonial and feminist perspectives on 68

Publication launch and collective reading

Languages: German + English

Montag, 22. Juli 2019, 17 – 20 h

Feminisms, postsocialisms, dissidence and diaspora reading group

Weitere Infos folgen

Riga, 10 May 2019

Dear S. and A.,

The Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art and District Berlin have been in dialogue for some years now, sharing a common understanding of political and social awareness and responsibility towards diverse art forms and their connections to society. We have shared thoughts on migration and archival research. In order to continue this dialogue in the form of an exhibition, we invite you to rethink together the history of the second half of the 20th century and the ensuing development of the contemporary world.

Several years ago, the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art initiated a research and exhibition project titled Portable Landscapes, examining stories of exiled and émigré Latvian and Baltic artists from the 20th century until today. Following the life stories of a number of artistic protagonists, the series of exhibitions explores the major centres of the Latvian diaspora: Paris, New York, West Berlin, Montreal, and the Swedish island of Gotland. By relating individual stories and chapters of migration to a common network situated within the broader context of 20th century art history and wider processes of migration and globalisation, the project aims to create an understanding of our contemporary world that is informed by these historical events. One of the project’s protagonists, curator and mail artist Valdis Āboliņš (1939-1984), whose family took a decision to emigrate form Latvia to Germany in 1944, puts into the spotlight the period of the Cold War and its complexity in relation to cultural production as Europe was divided in two by the Iron Curtain and the Wall divided Berlin. This leads us not only to rethink political and social tensions of the time, but also to analyse processes through the lens of Āboliņš as an insider and outsider in Berlin and Soviet Latvia.

Āboliņš moved to Berlin in 1974, when he took a position as an executive secretary at the New Association of Fine Arts (the nGbK, or neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst), the first and probably only fully democratically organised art association. His duties included project director responsibilities and organisation management, as well as active promotion and networking of the processes that were present in the nGbK. He couldn’t be active in any of the nGbK’s working groups, as the organisation’s philosophy didn’t allow the general secretary to be involved, in order to avoid conflicts of interest. The exception was exhibitions and events related to the Realismus Studio, where he could realise his leftist philosophy and put the emphasis on art that would discuss diverse aspects of the social and political environment at that time. Āboliņš formulated his leftist politics by merging Marxism, Maoism, Socialism, Trotskyism, and other leftist ideologies, but this made him something of an ideological maverick and set him apart from the mainstream Latvian exile community. He believed that active communication between Soviet Latvia and Latvians in exile should be developed, and was confident that the Latvian culture and art scene, despite ideological inconsistencies, should be perceived as one.

This also prompts us to contemplate the boundaries of countries and cultures, and to see the links of development between events in the Baltics and global processes. We are led to ask how well accounts of exile art can be integrated into local history, whether it is possible to look at histories that exist beyond the borders of national states, and how such histories are influencing global art processes now. With research and perspectives that illuminate contemporary artists and their experiences, we are eager to ask: how do you see and think about the processes of forced or freely chosen migration, and how should we talk about these processes in relation to history and the current day?

By rethinking Āboliņš as a curator, artist, and networker, as well as the working methods of the Realismus Studio, we wish the exhibition at the District Berlin to become a Diskussionsausstellung*: a place for a dialogue in which participants sit around a table, whether it is round or square or positioned against a wall. We have invited artists Inga Erdmane, Leonards Laganovskis, and Margo Zālīte to revisit their experiences as insiders and outsiders, and to open wider perspectives towards aspects of migration and displacement in Europe and beyond.

Leonards Laganovskis has taken as his point of departure his own experience of Berlin: East Berlin and West Berlin during the Cold War, and after the fall of the Wall the reunited city. While revisiting his work archive, he observed that codes and their patterns borrowed from political propaganda in the second half of the 20th century and used in his works repeat; just the political systems change and the overall red colour stays as a significant flag for revolution: an active, passive, or inner act of movement. In different forms and mutations, we can see similar systems repeatedly growing today. Political tensions escalate while nationalist movements become more stronger and legalise oppression towards those who seek for asylum. These processes activate the importance of knowledge, information and understanding of the contexts of the forced and freely chosen migration weather it is politically, economically or socially motivated. Aspects of displacement show in the photo series by Inga Erdmane where she has documented a tree in Paris growing in an artificial setting. Commenting on inhabitants’ urge to settle and to put down roots in their current place of residence, the artist later finds out that the character of the series won’t blossom. Even though the concerns that unite the works are the transformation of different political ideas and their possible radicalisation, the works also speak to the acceptance of diversity, to avant-garde moments in everyday life and finding oneself in this cosmopolitan world, as Margo Zālīte expresses in observations on her experience in Berlin, where she has lived for 10 years. In the context of the exhibition we have invited her to give a talk in which she will use autobiographical motifs to express her search for belonging in the course of the execution of her creative projects, throughout which she not only feels that she is an outsider in Berlin, but also sometimes is confronted by the male chauvinism that still dominates the artistic milieu.

The obscure flux connecting different points in this exhibition could be seen through the lens of a stranger, the one that seeks or belongs. His inner state is lost as he tries to find some codes, understandable signs of how to adapt reality into its own system of meaning. And what happens when points of departure are connected and we no longer think in opposites: stranger/local, immigrant/citizen, political/apolitical, us/them, West/East? The binary concept of thought is cancelled. This can not only settle you physically, but can also slow down rushing thoughts whenever you feel lost.

Thrilled to start the conversation.

Sincerely, A. and A.

……..

* The term was used in the first exhibition organised by Realismus Studio (1974), showing works by Juliane Borchert, Gerhard Faulhaber, Reinhard Pods, Peter Schunter, and Monika Sieveking). It frames a concept where an exhibition serves as a platform for discussing ideas, such as (in the case of the original exhibition) diverse aspects of realism in art.

Berlin, 31 May 2019

Dearests, A. and A.,

Thank you for your letter and please forgive us the terrible delay of our answer. Finally, we get to write to you from the day of Suza’s balcony where the bees have arrived alarmingly late this year and the night of Andrea’s desk next to the room where the child is asleep. We are looking forward to your arrival in a few weeks and to the exchanges about histories of diaspora and political dissidence (and their entanglements) in the context of the Cold War and post-/socialisms.

From Riga, Berlin, and Bochum you will bring materials from the archive of Valdis Āboliņš—the big monograph on his work and life that LCCA just published is already on our table—and works in response to this archive by Inga Erdmane, Leonards Laganovskis, and Margo Zālīte. We will await you all and Āboliņš’s ghost here with the artistic works by Elske Rosenfeld and Nguyen Phuong Linh & Tuan Mami, as well as documentary formats and research manifestations under the titles D’EST, Revolt She Said and Decolonizing 1968. The contributions we have invited might be read as counter-archives that de-centre, contaminate, and queer the dominant historical narratives that cross Portable Landscapes.

To think Portable Landscapes from here is also to ask ourselves WHERE we are, both in terms of time and of space:

TIME: The past weeks and months, as well as the times to come, were and are lived under the stars of transformation and struggle. In a night two weeks ago that was filled with gestures, oracles and songs, rituals, dance, memories, readings, imaginations, warnings, and laughter towards our transformation, District emerged anew as a collective entity and a commons under the name District * School Without Center. While engaged in nurturing queer, feminist and anti-colonial futures, District is under threat existentially and spatially, a condition we share with many collectives, communities and spaces in this city and in this world. You have been witness to our struggles and exhaustions over the past year, and we are thankful for your solidarity and for keeping us on board throughout a bumpy ride with multiple changes, absences and delays. At this point in time, we are only midway in the fight of holding on to our space and to the possibility of continuing our work—and this liminal place and shifting ground might well be the habitat for our future, which is why we need to learn from ways of living developed within and across various borderlands. Certainly it is this liminal time and place in which Portable Landscapes will happen.

SPACE: Phuong Linh’s collaborative installation White Mist in Foreign Country, which inhabits District since April this year and will continue within Portable Landscapes, makes present how landscapes become portable through diasporic movements and memory, ecological bonds, colonial extraction, and contamination. Through the multiple works that come together in the installation, which also hosts a work by the artist Tuan Mami, Linh links her research into the histories, psychoscapes and environments of Vietnamese migration in Berlin to the post-/colonial ecologies and multi-species socialities in Vietnam. Her installation proposes a white fog dense with microparticles of bodies, earths, plastics, and toxins—a fog that drifts through nail salons around the world and moves across landscapes marked by mining—as an environmental figure that connects experiences of life, death, and states in between, across atmospheres and communities haunted by different manifestations of extractivism. In the context of Portable Landscapes, Linh’s and Tuan Mami’s works also stand as a reminder of the histories of Vietnamese migration and continued ecological trauma related to colonialism and its continuity in the American War in Vietnam, which hugely influenced the political protest movements in the 1960s and 1970s.

Thinking about the contexts and relational fields of Portable Landscapes here in Berlin, and in an attempt of conscious re-sourcing (also a strategy of dealing with funding cuts and unsuccessful project funding applications), we are channelling some of the situated and intersectional processes of working collaboratively on unmaking histories that have been developed at District between 2017 and today.

Since 2018, Andrea, together with Katharina Koch and Dorothea Nold from alpha nova & galerie futura, has been working with the artists, curators, theorists, and activists Sharon Adler, Liz Bachhuber, Madeleine Bernstorff, Anguezomo Mba Bikoro, Lisa Glauer, Karina Griffith (District Studio and Research Grant ‘Decolonizing 68’), Natasha A. Kelly, Katharina Koch and Dorothea Nold (alpha nova & galerie futura), Azade Köker, Martina Kofer, Corina S. Kwami, Pınar Öğrenci, Peggy Piesche, Elianna Renner, Robert Schmidt-Matt, Gabriele Schor, Valeria Schulte-Fischedick, Kelvin Sholar, Elżbieta Sternlicht, Merle Stöver, and Anja Zimmermann on a series of research-based historical interventions into the dominant memory of the 1960s protest movements in West Germany and beyond. The project and the resulting publication are a platform to recapitulate herstories of the 1960s and 1970s resistances through contemporary work by migrant, diasporic, Jewish, and Black women and women of colour. Within Portable Landscapes, this contribution aims at widening and reconnecting the contexts and landscapes made present through Āboliņš’s legacy of political and artistic activities of the ‘60s and ‘70s in Aachen and West Berlin. The scholar and activist Peggy Piesche initiated a film portrait series titled Decolonize 1968!, dedicated to Black and PoC contemporary witnesses of the events of 1968, especially in West Germany. In the project and her related text, she references the contemporary witnesses and activists Fasia Jansen, Ilona Lagrene, Arfasse Gamada, and Sevim Çelebi-Gottschlich., and thus makes present those who often, because of their historical involvement in anti-colonial, anti-racist and anti-imperialist struggles in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, set decisive impulses in Germany. For Piesche, the life stories of the portrayed activists do not stand as individual cases for themselves, but refer to different collective experiences.

Our conversations around Portable Landscapes started in snowy Riga in early spring 2017 with Elske Rosenfeld and Suza visiting you at LCCA to exchange knowledge and possible approaches towards this collaboration. Ieva Astahovska and Antra introduced your research on Āboliņš and materials from his archive that had been donated to the LCCA. Elske shared her research on the 1989 revolution in the GDR, the emancipatory political movements that led to these events, and the dismantling of their social and political potential in the colonial dynamics of the German reunification. Based on materials from 1989-90 and more recent global uprisings, Elske investigates in her work how collective political imagination and action manifest and leave bodily traces in those involved. Her two works in the exhibition are linked in their different expressions of bodies as archives and their relational focus on Ulrike Poppe Ingrid Köppe and Gabriele Stötzer, all three protagonists of the political and artistic underground in the GDR. Her contribution also resonates with the viewing station of D’EST: A Multi-Curatorial Online Platform for Video Art from the Former ‘East’ and ‘West’, which makes this young archive of the histories of post-/socialist transformation mapped through feminist perspectives accessible in the exhibition.

The day after the presentations and discussions, the four of us looked at materials from Āboliņš’s archive in a space that had just been used by a group of Riga-based feminists you were collaborating with. In retrospect, this moment of overlap opens up many questions: what was Āboliņš’s relation to feminism? Why does the desire to rethink modern art history, as you write, take departure from the legacy of a white male artist (rather than from feminist ancestors, for example) and the contested myths of Western avant-garde? Why does a women-run art center like yours, which is interested in diverse art forms and their relation to society, actively produce this legacy? What does it mean to canonise Āboliņš in Latvian art history in a moment of nationalist celebration and memorialisation of 100 years of the Latvian nation? What does the swallowing of diasporic cultures into the national body do? And whose diasporic histories and cultures are desired by the national body, or, what is the relationship between the diasporic or post-/migrant communities outside and inside the national borders of Latvia?

Among the many things Elske and Suza learned during the time in Riga in 2017, there are a few micro-moments, subjective memories that speak a little to the above questions about the relationship between diaspora and nation. One was tender: a man who had grown up with Āboliņš in West Germany spoke about how your research was forcing him to remember their closeness, their communism, and their cross-border political initiatives, and how these long dormant memories demanded for him to think about what they meant for him today. One felt rather uncanny: one of the invited speakers, who like Āboliņš and his friend had been a member in the exile Latvian youth organisation in the ‘60s and ‘70s and seemed to be very active in Latvian politics today, made it clear that there was a strong relationship between the political organising of the time and the conservative nationalism post-independence. The third one was dense with entanglements: you organised a meeting in the LCCA office with the artist Andrejs Strokins, who showed us a collection of private photo albums beginning in the 1920s or ‘30s that he was interested in as unwanted histories. Rarely navigated cross-connections emerged from the pictures we encountered, such as the intimate realities of (often military- and labour-related) migration from different parts of the Soviet Union, as well as local pre-Soviet postures of fascist masculinity or the aristocratic architectures of land and industrial ownership. While the first type of images led us to a conversation about Riga’s Bolderāja neighbourhood by the Baltic shore, which is inhabited mostly by Russian-speaking communities and is a battleground of growing environmental activism against the pollution of sea and land by local manifestations of the military-industrial complex, the second made us aware that among the many people who fled from the Baltics at the end of the Second World War in fear of Stalinist persecution and repression were also Latvian fascists and privileged families whose longing towards the landscapes they left behind was one of denied ownership, like capitalist phantom pain.

Within our small exhibition many of these issues are not addressed directly through the contributions but emanate from the political and historical landscapes they carry with them. Continuing the polyphonic form of our multiple meetings, conversations, and letters, we hope that Portable Landscapes: Unweaving the Iron Curtain will work more like an experimental assembly for discussing—yes! to your idea of a Diskussionsausstellung —feeling our way into, synthesising and dis/agreeing with the relationships and cultural meanings between the different elements and contexts: a space of encounters and frictions with gaps and yet unforeseeable resonances, in which we might find shared grounds and practices for unweaving and unravelling, for moving and looping below, sideways, across, and beyond the ossified threads of History with a capital H.

Warmly from a day that has become late night, and looking forward to your next letter,

A. and S.

Die Ausstellung ist Teil der Recherche- und Ausstellungsserie “Portable Landscapes” des Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art und eine der Veranstaltungen der lettischen Hundertjahrfeiern in Deutschland. Die Beiträge von D’EST, Nguyen Phuong Linh und Revolt She Said wurden entwickelt in Zusammenarbeit mit und unterstützt von der Senatskanzlei von Berlin – Kulturelle Angelegenheiten, dem Rumänisches Kulturinstitut, der Administration of the National Cultural Fund (AFCN), atelier 35, Moscow Museum of Modern Art (MMOMA), Goethe Institut Moskau, Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Filmwerkstatt Düsseldorf, Galeria Miejska Arsenał, Poznań, Pawilon, Poznań, und dem Neuer Berliner Kunstverein Video-Forum (D’EST), ifa (Nguyen Phuong Linh) und alpha nova & galerie futura (Revolt She Said).